His host was Bernard Baruch, who invited Hopkins to spend some time at Hobcaw Barony, his estate near the junction of the Waccamaw and Pee Dee Rivers. It was a storybook place, with rolling lawns, a manor house, wild areas given over to game and fish, and trees dripping with Spanish moss. And Baruch, as elder statesman par excellence, could give Hopkins advice on his political future

Baruch, however, was preoccupied with the growing threat of war. Hopkins had no special competence in foreign affairs. Like any other intelligent man of the period, he had read the papers when he had the time and he had talked with Roosevelt, but his professional life had been almost entirely directed to domestic problems

While Hopkins was at Hobeaw, Hitler, on March 14, contemptuously tore up the Munich pact and took over the rest of Czechoslovakia. This act gave Baruch his opportunity, and he pounded away at the theme that the United States was inextricably interwoven with European affairs, whether the people liked it or not. He told him of the one man in England who knew the truth and who was kept sidelined for telling it. This man, Winston Churchill, had warned Baruch the previous year, “War is coming very soon. We will be in it and you will be in it You will be running the show over there, but I will be on the sidelines over here.”24 Hopkins, who knew of Churchill only as a name, may have taken little note of that statement, but he should have. Churchill was to become one of his closest friends, and Hopkins, rather than Baruch, would be to a great extent “running the show” in the United States.

Hopkins’ education in foreign affairs continued when he went for a vacation with Roosevelt to Warm Springs. Before departing, he wrote Lewis about how poorly he had been feeling after a “very bad case of intestinal flu.” He sounded depressed and tired as he went on to tell of his hopes to get a house in Grinnell, in which to “spend my declining years.” He went on:

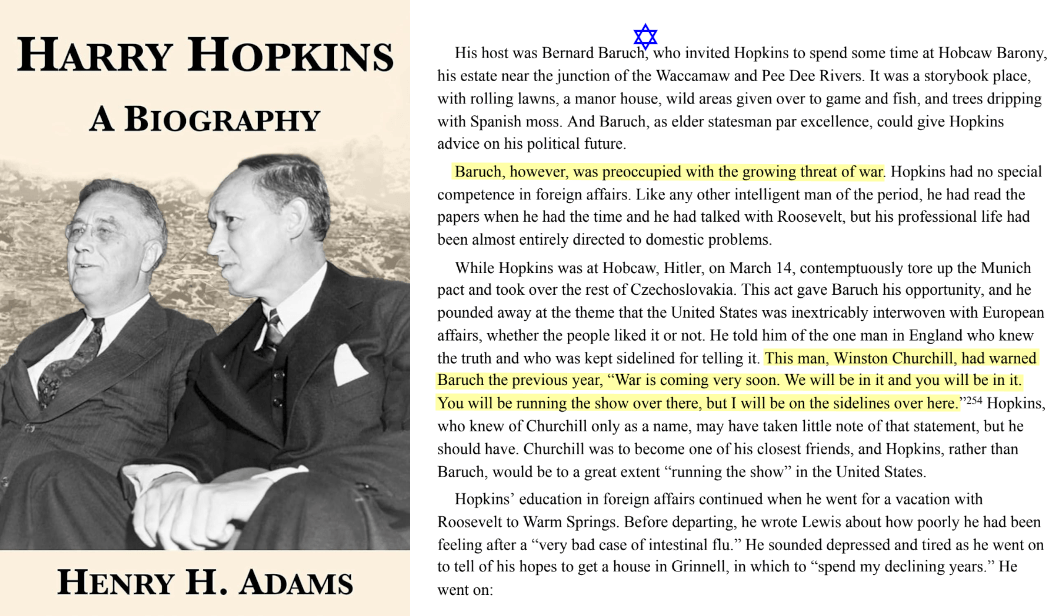

Harry Hopkins: A Biography, Henry Hitch Adams